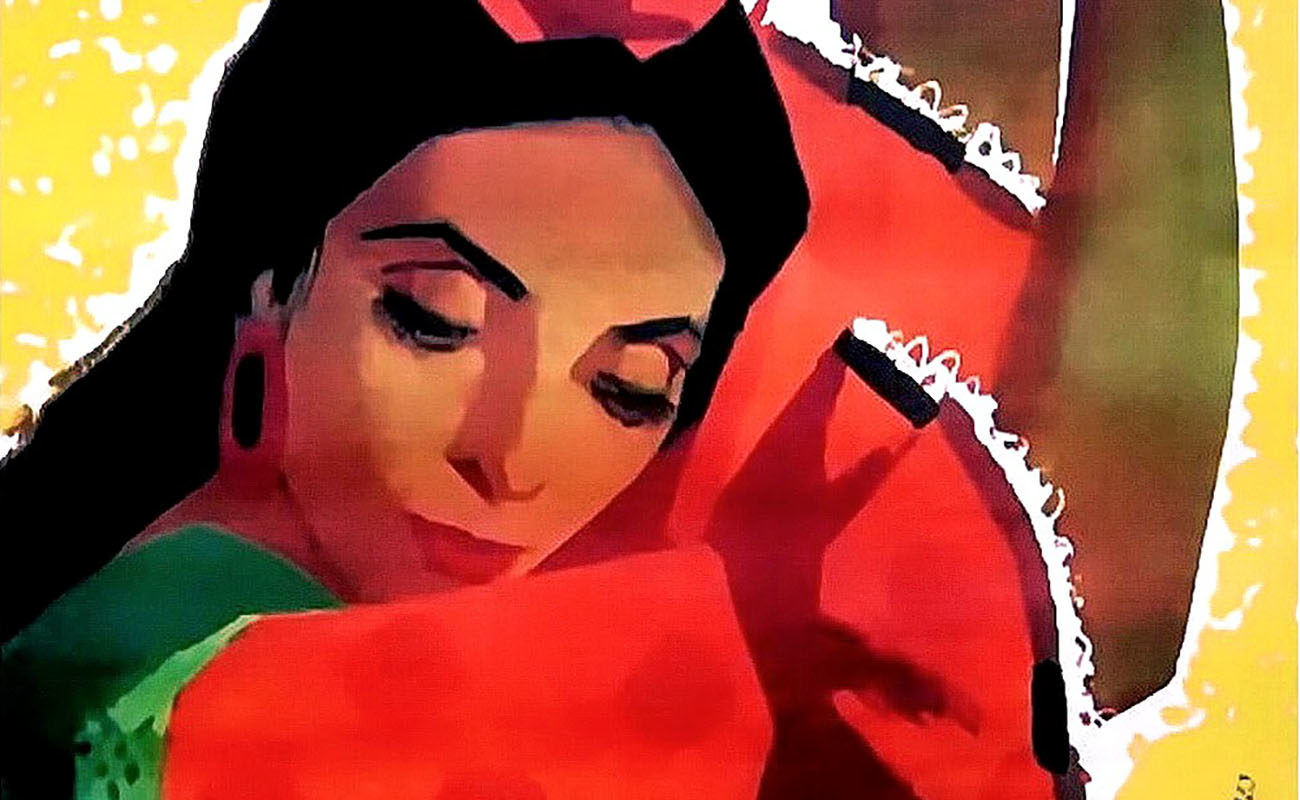

A Time Capsule – Flamenco’s evolution as seen 50 years ago

In June of 1968, exactly 50 years ago this month, I wrote the following article, “The Evolution of Flamenco” in a newsletter devoted to flamenco issues, musing upon the future of flamenco. This was right before Paco and Camarón burst upon the scene, and no one suspected the profound changes about to take place. Surprisingly, the text doesn’t contain anything

Many flamencos hold the common misconception that this is a static, fully-developed art that has barely changed for hundreds of years, however such is not the case. In fact, flamenco as we know it has only existed for less than 100 years, and the breeding-places of flamenco are as prolific today as ever.

When we hear words such as “pure”, “authentic”, “real”, etc., applied to flamenco, they are referring to the flamenco which was accepted at an earlier time in a particular area, among a certain group of artists. These are general terms since what may be authentic for some, is modern or commercial for others. Innovators in flamenco tend to be promptly accused of lack of knowledge.

The constant evolution that has brought flamenco to modern times surprises most people. Let’s look at some examples in dance. One of the most popular flamenco dance forms, the siguiriyas, was only first danced in 1940 by Vicente Escudero, one of flamenco’s most revolutionary artists, who went so far as to experiment with the surrealistic possibilities of the dance. Not many years later, Carmen Amaya added castanets, much to the disapproval of many old-timers, some of whom today have not yet embraced the dance of siguiriyas.

José Greco is credited with the development of the long break or “llamada” in farruca, not to mention many other contributions to the evolution of theater flamenco inspired in the concepts of Pilar López. Carmen Amaya was the first to dance an “escobilla” or heelwork section without guitar accompaniment. Today, this practice is not only acceptable, but fashionable in dances of the alegrías cantinas group. She is also credited with creating the dance of taranto in the 1940s. Roberto Iglesias, the choreographic genius, worked with pantomime and jazz piano. Antonio Ruiz Soler was the first to dance the martinete, an even greater breakthrough since it was then, and still is, the only cante without musical accompaniment which is danced.

These are just a few examples of people who have tapped new sources thereby expanding the art and enabling its evolution.

In flamenco singing (cante), from the subtlety of La Niña de los Peines, and the flowery style of Chacón of some years back, today we are more apt to hear the open-throated natural vocal style of Fernanda and Bernarda de Utrera and Antonio Mairena. The cante is always evolving, and in fact has been in nearly all cases the inspiration for new creations in flamenco dance, and even guitar. Nearly all the song-forms, even those without a measured rhythm, have been danced, and most of this has occurred only within the last 30 to 40 years.

Right alongside the cante, its very backbone and often the center of inspiration, is the musician. Decades ago it was Ramón Montoya who adapted classical techniques to the flamenco guitar, making it a true virtuoso instrument which the maestro Sabicas would develop further. Today, you might hear Arturo Pavón play piano accompaniment for malagueñas identical to the guitar, or Pedro Iturralde play soleá on his saxophone.

The question is, just where is this evolution taking us? Consider the three main outlets of flamenco: 1) the concert stage with its large, impersonal audience and group choreographies, 2) the typical night-club with its drinking clientele, and 3) the private fiesta. All three have advantages and disadvantages, and have developed forms which best enable the artists to express themselves in the respective situations. The beautiful line, amazing technique and expansive movements of the concert stage; the intense solos and couple dancing of the night-club, and the open-ended free-wheeling private party where anything can happen.

Where the art might go from here depends on the needs of the artists which, despite what most people might think, are not only monetary. In the opinion of Donn Pohren (author of “Art of Flamenco”, 1962), “we have just a few years left, perhaps, with luck, to the end of this century, to savor a living, breathing, significant art of flamenco”, although dedicated people throughout the world are working to preserve the past, as well as the present, so that in the continuing evolution of flamenco, there may be guidelines, meaningful reflection and inspiration.

Estela Zatania, June, 1968

Bulletin of the Flamenco Information Service Library